In Darkness, a Language Forms

Written by Jadine Collingwood

Essay

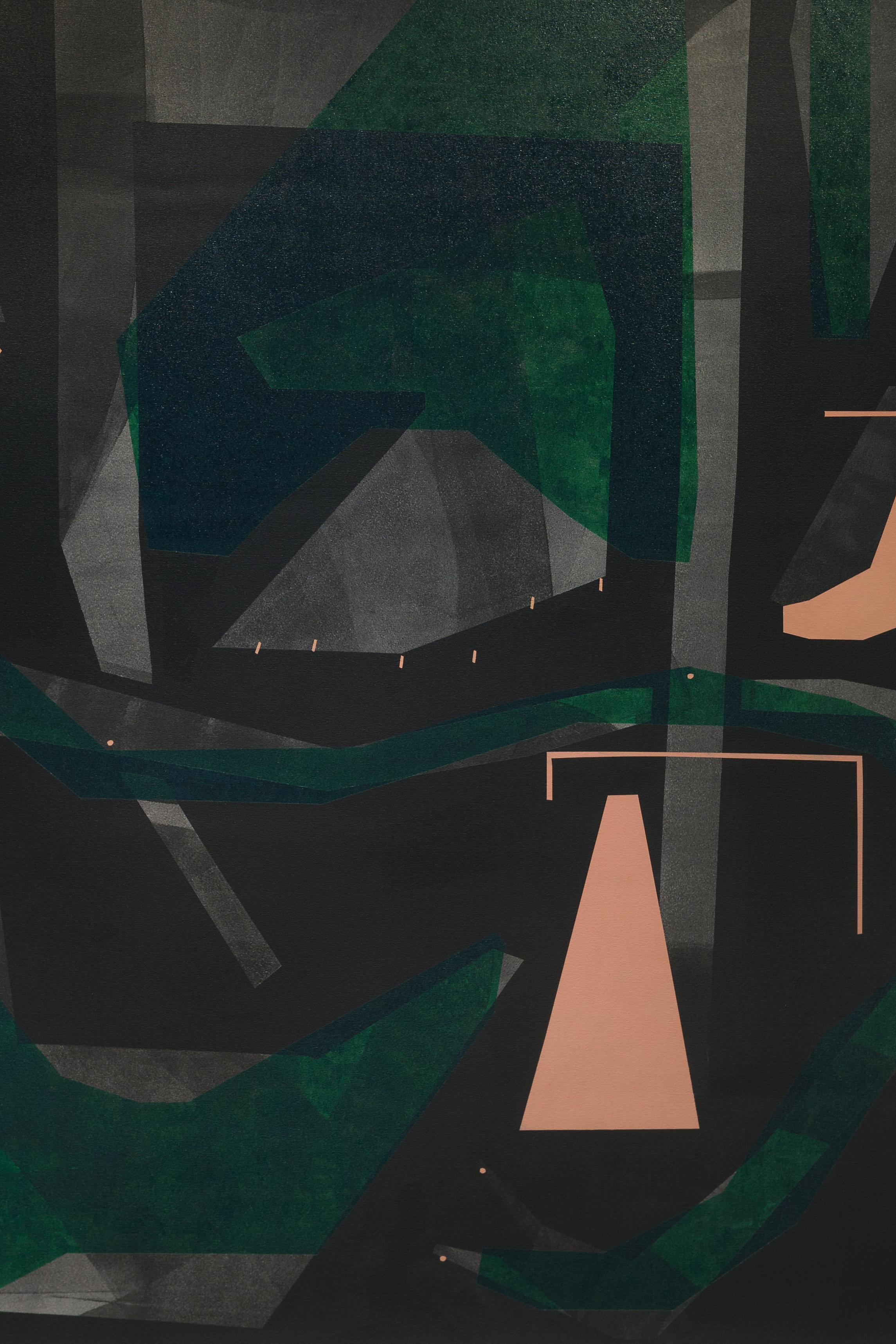

Caroline Kent, Further and Farther Than One Expects, 2015. Acrylic on unstretched canvas; 72 × 96 in. Collection of the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, T. B. Walker Acquisition Fund, 2016. Courtesy of the Artist; PATRON Gallery, Chicago; Casey Kaplan, New York; and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles.

Photo: Rik Sfera.We begin in the dark. For many years, artist Caroline Kent has used darkness as a starting point, a ground zero for a nuanced exploration of abstraction, language, and the limits of communication. There is, of course, the literal, material darkness of the monumental black paintings that form the centerpiece of Kent's practice. Assuming an almost architectural scale, these expansive canvases behave spatially, manifesting as open voids that implicate the beholder's body. It is in this sense that the artist suggests, “The façade of painting is merely a veil, an icon, a Twilight Zone entrance, or an exit, into perceiving, without the trappings of being able to or having to name a thing.”1 Without being able to or having to name a thing—Kent's work invites us into the space of the unknown. In the dark, a special kind of language begins to take shape: one that challenges conventional understanding and resists easy interpretation.

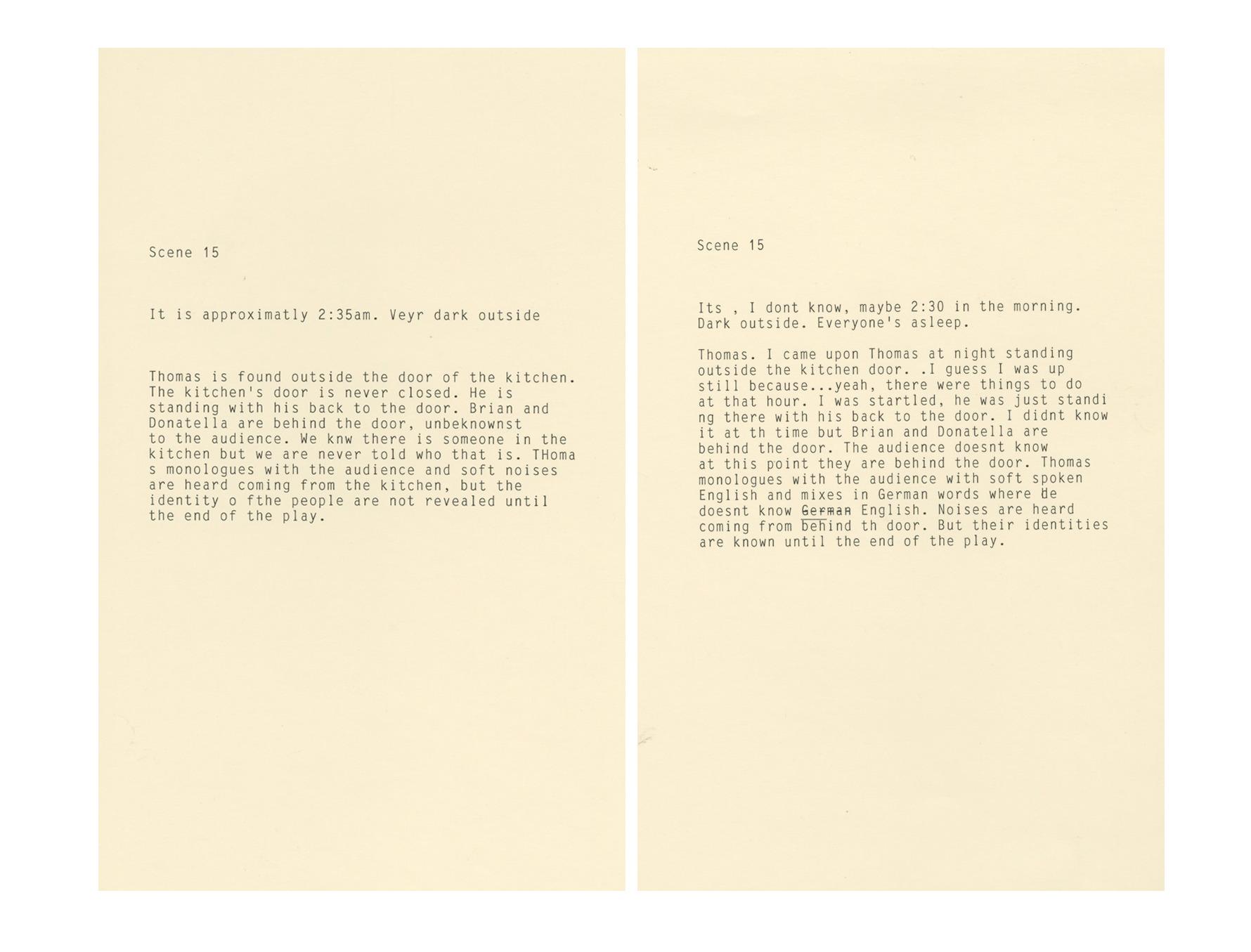

Caroline Kent, Scene 15, 2013. Typewriter on paper; 22 x 17 in.

Courtesy of the Artist; PATRON Gallery, Chicago; Casey Kaplan, New York; and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Caroline KentOver the years, Kent has developed an abstract painting vocabulary that she employs like a language, albeit one that tests the limits of legibility. The artist frequently recalls that her fascination with language stems from early encounters with foreign films, where she observed the slippages between seeing images on the screen, hearing an unfamiliar language, and reading its translation in subtitles. Those instances of breakdown, mistranslation, or omission were instructive, piquing Kent's interest in the moments when language refuses to behave in the ways we might expect. The artist's earliest works experiment with using language to articulate brief cinematic scenes of Kent's own imagining. The short, typewritten texts maintain grammatical and spelling errors that communicate the writer's sense of urgency. Elusive and enigmatic, these screenplays place action just out of view, explicitly withholding key details. For example, the work Scene 15 (2013) describes, “We knw there is someone in the kitchen but we are never told who that is.” Fittingly, the moment unfolds at a late hour, “Veyr dark outside,” as if darkness were an analogue to our access to information about the scene. In these early screenplays, Kent toyed with the transparency and opacity of language, its capacity to create meaning, but also its potential to omit or conceal.

Caroline Kent, Installation view, A Form Walks Toward You In The Dark, 2020, The TCNJ Art Gallery, Ewing, New Jersey

Courtesy of the Artist; PATRON Gallery, Chicago; Casey Kaplan, New York; and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: George W ChevalierWhen Kent turned to abstract painting she continued to investigate those limits of legibility. As the artist explains, “When I started making abstract paintings, I was fascinated by the fact that you can create a visual language that is coded. Where it puts everyone on the outside of interpretive meaning.”2 Of course, Kent's chosen medium of abstract painting comes with considerable baggage; not least of all, modernist abstraction's claims of universal legibility. Pure shape and color, it has been claimed, could transcend social, cultural, and geographic differences. No matter that modernism's much-vaunted neutrality centered on a very specific subject position, most often assumed to be Euro-American, white, and male. If the language of modernist abstraction was one based on a set of codes shared by a select few, Kent set out to develop a language unmoored from such convention, one that would put everyone in the position of the outsider. Wresting language from its public functions, Kent explores how a private, invented language can forge new modes of intimacy, affiliation, and belonging.

Installation view, Chicago Works: Caroline Kent, MCA Chicago. August 3, 2021–April 3, 2022

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA ChicagoThe foundations of Kent's invented language date to 2014, when the artist first began assembling an ongoing archive of small paintings on 30-by-22-inch sheets of paper, coated with black gesso. Challenging herself to avoid repetition, Kent composes her pictures by cutting improvised shapes from sheets of paper, a technique that she describes as a “quick, immediate way to bring forth a form.”3 The artist arranges these hard-edged geometric shapes into dynamic configurations, which then serve as guides for her paintings. Numbering in the hundreds and growing, these small paintings constitute an expansive library of visual forms from which Kent draws to make subsequent works, including the larger black paintings as well as sculptures, installations, and performances.

Caroline Kent, What it might mean to live among shadows, 2021. Acrylic on unstretched canvas

Courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photo: Ian AceFor this Chicago Works exhibition, Kent developed an immersive installation titled Victoria/Veronica: Making Room. The project takes as its starting point a fictional set of identical twins who communicate telepathically across two distinct environments: a writing room and a reading lounge. While physically distanced, the twins are united by the secret language they share. The museum's galleries bear the features of a quasi-domestic space—plush carpet, walnut wood furnishings, canvas-covered books, and potted plants approximate everyday household items. Infusing the ordinary with an air of the supernatural, the twins transform these familiar objects into carriers of telepathic communication. Traces of their conversation appear in the form of abstract shapes that travel across the surfaces of drawings, paintings, objects, furniture, and walls. Large cutouts form recesses in the walls, as if the telekinetic force of the twins' shared language created an imprint in the building's very architecture. Geometric inlays mark the surface of a wooden desk and bookshelf, suggesting that the twins' psychic language has also physically altered the furnishings. Throughout the space, synthetic plants blur the line between the real and artificial; listen carefully, and you'll hear a low-frequency hum emanating from their leaves. Like Kent's visual language, the static noises broadcast by the plants do not refer to anything in particular. Instead, the crackling speakers in both spaces evoke a slightly paranormal atmosphere, as if someone or something were attempting to communicate from beyond.

The supernatural elements of the installation set the stage for our encounter with a language that refuses to behave in the ways we might expect. It is in this respect that Kent has likened the experience of her work to being transported to the twilight zone:

The twilight zone is not a destination people can get on a train and go to. It's not even a destination that one can go to willingly on their own. But one finds oneself in the twilight zone. And they find themselves there because something subtly has shifted [. . .] a paradigm shift happens, their old paradigm is gone, it has slipped away and there's a new paradigm that they have crossed over into and that new paradigm can feel terrifying.4

Kent transports viewers into a parallel universe, a place where the ordinary rules of language no longer apply. The transition into the exhibition space is striking; a lush dark green cloaks the walls and floors, enveloping viewers within deep saturated color. Providing a stark contrast to the museum’s traditional white-cube gallery spaces—those sacred temples to modernist abstraction—the color gives one the feeling of passing through a threshold and into a dark abyss.

Caroline Kent What it might mean to live among shadows (detail), 2021 Acrylic on unstretched canvas

Courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photo: Ian AceMuch like the hushed whispers uttered under the cover of nightfall, Kent suggests that darkness facilitates a kind of communicative intimacy: “Darkness becomes a kind of state, or kind of frequency, or a kind of presence—a context that is very inviting for telepathy to take place because one lowers their inhibitions. One feels a kind of security or safety in the dark. That provides a space for magic to happen, for this special relationship to unfold. I think about these twins using the darkness in service to their communication.”5 Darkness produces conditions that allow language to behave differently, connecting the twins across space and time.

Installation view, Chicago Works: Caroline Kent, MCA Chicago August 3, 2021–April 3, 2022

Courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photo: Ian AceFor the exhibition, Kent created a new suite of paintings, including the two large-scale canvases that anchor each gallery space. The paintings have an insistent duration, alluding to the moment just before and after an image begins to take shape. Here, the blackness of the canvas functions like a transition in a film: forms appear to fade in from black, as if emerging from darkness. “What it might mean to live among shadows” (2021) is a nine-foot painting populated with an all-over constellation of abstract geometric shapes. Attached to the wall only by its top edge, the unstretched canvas gently curves away from the wall, like a piece of paper or fabric. Kent typically marks out the outlines of forms with masking tape and then fills them in with acrylic paint. This process produces a sharp, clean edge that separates the shapes from the ground within which they appear. Laid out with almost grid-like precision, the composition approximates the internal logic of a map or diagram. Despite this initial sense of a system or structure, any attempt to assign meaning to the various painted elements immediately breaks down.

Caroline Kent Poem/Plot 1, 2021 Wood, cement, and acrylic on linen

Courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photo: Ian AceTransparency and opacity make it difficult to plainly distinguish shape, shadow, and ground. The surface of the painting consists of consecutive layers of overlapping shapes, beginning with a thin veil of dusty charcoal forms. Painted in varying degrees of opacity, areas of the black substrate puncture through to the surface, making the gray forms appear to dissolve into the painting's ground. At moments, the charcoal functions like a shadow; a narrow ribbon of paint snakes through the composition, echoing the curvature of a winding dark-green shape. However, the integrity of the shadow breaks down as the translucent layer of green allows areas of black and gray to peek through. What's more, these indeterminate, unbounded forms compete with another signification system altogether. Within the same painting, an opaque layer of coral pink is emphatic in comparison, stamping out the layers below and reaffirming the picture's flatness. In Kent's treatment, transparency and opacity become ciphers for a larger exploration of communication systems, metaphors for how language reveals and conceals.

Installation view, Chicago Works: Caroline Kent, MCA Chicago August 3, 2021–April 3, 2022

Courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photo: Ian AceIndeed, in the artist's hands, language acts—misbehaves, even. “[The language] extends beyond the frame and goes out into the room, and it manifests in the sculptures, and the walls, and other objects. It moves around and it doesn't sit still,” Kent explains.6 As the language moves through space it designates, announces, inscribes, discloses, duplicates, omits, fragments, effaces, and illuminates. It is precisely language's doing that has become a central preoccupation of Kent's practice. In Victoria/Veronica: Making Room, language performs a social function, as a private dialogue generates new modes of affiliation and belonging. As Kent explains:

Within the space of the abbreviation is where I found that this language seemed most fitting between the sisters. So yes, there's twin language, which is a secret kind of coded language that twins speak in, but I thought more importantly than that maybe-obvious connection, is that when two people are kin and very intimate and know each other a long time, there becomes an established way of talking and that's through these different kinds of intimate gestures, whether those are physical gestures of body language or gestures of speaking and the way they speak to one another.7

Installation view, How Objects Move Through Walls, 2018, Company Projects, Minneapolis.

Courtesy of the Artist; PATRON Gallery, Chicago; Casey Kaplan, New York; and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Leah Eldelman-BrierAlthough we cannot access the content of the twins' messages, we sense a certain amount of care and attention, as their communication marks items of personal significance, disclosing the intimacy of a language built from shared memories and experiences. The exhibition playfully oscillates between the closeness of this language and our distance from it, giving us a glimpse of the twins' private connection while simultaneously maintaining our position as outsiders. In the reading room, a wooden bookshelf contains dozens of books wrapped in linen cloth. Artifacts of the past, the books consist of thrift-store finds that have been discarded, presumably because their contents are outdated or no longer relevant. Repurposed by Kent as vehicles for the twins' communication, the cloth covers are painted with cryptic shapes and symbols. Using a reduced catalogue of forms, often a single shape or two, the book covers assume an almost didactic function, as if they were meant to explain the books' contents as clearly as possible—more like a rebus or teaching aid. However, transformed into visual objects, the books can no longer be read, ultimately leaving their contents a mystery and barring access to their textual material.

Installation view, Chicago Works: Caroline Kent, MCA Chicago, August 3, 2021–April 3, 2022.

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.Similarly, the repetition of geometric forms throughout the exhibition conveys a sense of systematicity, enticing viewers to try to decode the language's meaning. On the wall opposite the bookshelf, the small diptych “Poem/Plot 1” (2021) brings together multiple iterations of the same shape. On the upper portion of the work, a light, natural-colored linen canvas contains shapes painted in pink and green. A narrow, rectilinear shape pulled from this composition is repeated in the lower half of the diptych, this time pressed into a black slab of cement. Finally, a positive mold of the same shape appears as a cement sculpture placed within a small recess in the adjacent wall. These systems of signification compete with one another, making it difficult to assign a singular function to the rectilinear shape—stamped in dark green on raw linen, the shape feels like an emphatic command; pressed as a shallow shape in black cement, the shape becomes barely discernible, almost like a whisper or trace; enshrined high up in an alcove and softly lit, the shape assumes a reverence typically reserved for religious icons.8 Rather than resolve these different readings, Kent amplifies their contrasts, leaving definitive meaning just out of reach. As we perambulate in conceptual darkness, we witness a language in the process of becoming.

Caroline Kent and Nate Young, Writing Desk, 2021. Wood. Installation view, Chicago Works: Caroline Kent, MCA Chicago, August 3, 2021–April 3, 2022.

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.This process of becoming is precisely the point—Kent's practice is oriented toward future possibilities, it exists without having to name. If the black abyss conjured by Kent's canvases suggests another dimension, her practice as a whole points to a perpetual beyond. In its everyday uses, language categorizes, regulates, and reifies. Against this fixity, Kent's practice makes room for openness, multiplicity, and spontaneity. As viewers, we are invited to participate in a temporal exercise; “reading the room” requires us to take note of that which we see, but also that which has yet to arrive. It is in this respect that Kent likens her installation to scenography: “I'm trying to get people in the round, theater in the round is all encompassing, it's circular . . . I'm thinking about being in the round with this exhibition; I'm trying to account for all the surfaces. This scenography provides a framework that is in service to a desire for the observer to think about what could be performed in the space.”9 Frustrating a linear progression through the exhibition, Kent's network of signs and symbols asks viewers to review, reevaluate, and edit their perceptions in real time. In previous works, Kent has explicitly explored the link between notation and movement, using her abstract paintings as scores for choreographic performances. Here, the incitement to perform remains implicit, an open invitation to imagine an unfolding narrative drama.

Installation view, Chicago Works: Caroline Kent, MCA Chicago August 3, 2021–April 3, 2022

Courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photo: Ian AceAs such, Kent's works are not merely carriers for the twins' communication, they also function as props, or even prompts, for future activations. Throughout the exhibition, a system of lines and dots act like punctuation, marking points of emphasis or pause. On the floor, patches of lighter green carpet form “l”-shapes, underscoring the area surrounding the sculptures. Like parentheses or quotation marks, these forms function as empty signifiers, containers waiting to hold a future language. In the second gallery, a small wooden desk signals a space for writing. Facing the entrance, the desk is positioned in a way that invites viewers to approach it like a podium or lectern. Insofar as we treat it as such, we accept a call to action. As Kent explains, “The desk is a placeholder for future kinds of moves … It is a way to make a space in the exhibition for a future thing.”10 A tabula rasa, a blank page, a space to create a language of our own, the writing desk marks a potential site of production, an open void oriented toward the bubbling possibilities of an imagined future.

Footnotes

- Artist Statement, Kohn Gallery, kohngallery.com/caroline_kent

- Caroline Kent, “A Form Walks Toward You in the Dark” (public lecture, St. Catherine's University, St. Paul, MN, October 15, 2018), youtu.be/IQNBP7pqZSA

- Quoted in Jenn Pelly, “An Artist Who Paints in Cryptic Pastel Symbols,” New York Times (November 16, 2020), nytimes.com/2020/11/16/t-magazine/caroline-kent.html

- Conversation with author, May 3, 2021.

- Conversation with author, May 3, 2021.

- Conversation with author, May 3, 2021.

- Conversation with author, May 3, 2021.

- For more on the relationship between Kent's work and religious icons, see Nicole Watson, “Gateways to the where: Investigating new territories in the work of Caroline Kent,” St. Catherine University, gallery.stkate.edu/exhibitions/beyond-the-karman-line

- Conversation with author, May 3, 2021.

- Conversation with author, May 3, 2021.

Funding

Generous support is provided by the Sandra and Jack Guthman Chicago Works Exhibition Fund, the Zell Family Foundation, Anne L. Kaplan, Cari and Michael Sacks, R. H. Defares, Rena and Daniel Sternberg, Charlotte Cramer Wagner and Herbert S. Wagner III of the Wagner Foundation, and Anonymous.

Additional support provided by PATRON, Chicago.

This exhibition is supported by the Women Artists Initiative, a philanthropic commitment to further equity across gender lines and promote the work and ideas of women artists.

CREDITS

This digital brochure was published on the occasion of the exhibition Chicago Works: Caroline Kent, organized by Jadine Collingwood, Assistant Curator, and presented from , to , in the Sternberg and Rabin galleries on the museum's third floor.

- DIRECTOR of CONTENT STRATEGY

- Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan

- MANAGER of RIGHTS and IMAGES

- Katie Levy

- EDITOR

- Leah Froats

- ASSISTANT CURATOR

- Jadine Collingwood

- DESIGN and PROGRAMMING

- Alexander Shoup

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago is a nonprofit, tax-exempt organization accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. The museum is generously supported by its Board of Trustees; individual and corporate members; private and corporate foundations, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; and government agencies. Programming is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency.

Free admission for 18 and under is generously provided by Liz and Eric Lefkofsky.

The MCA is a proud member of Museums in the Park and receives major support from the Chicago Park District.

© 2021 by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including photocopy, recording, or any other information-storage-and-retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Images found on this site are for educational use and are published under the umbrella of the Fair Use doctrine.

MCA Chicago

Museum of

Contemporary Art

Chicago