ACT UP: The State of Museum Activism

blog intro

This past weekend, we celebrated Pride month with Chicago's 47th Pride Parade. Held each year in cities across the United States, the Pride parade publicly commemorates the Stonewall riots of 1969, when people chose to stand up, fight back, and claim public pride in their identity. Today we examine Pride in the context of the contemporary art world.

on pride

People often classify themselves with false binaries—gay or straight, black or white, man or woman. It's conversational short hand, and illustrates why Pride is important to the LGBTQIA community. Today marks the 47th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, the first time the LGBTQ community fought back by refusing to stay silent in a world that wished we remained invisible. Pride is a moment when we make visible the people who exist in the gray space between and beyond these poles. By celebrating Pride every June, we continue to publicly affirm the plurality of our community. As much as Pride is a celebration, it's also an act of defiance that functions like a massive visibility campaign.

Instagram post on Silence = Death

link

Instagram post of Act up parade

link

on arts activism

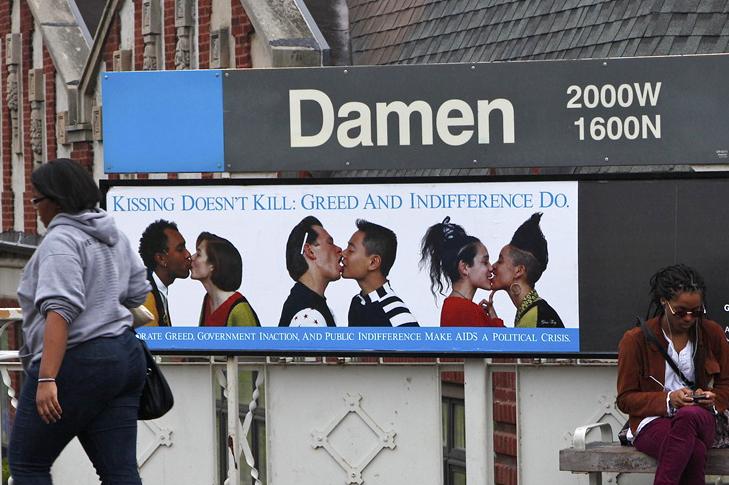

Visibility has always been important, politically, for the LGBT community. In the 1980s, artists collectives like ACT UP, Gran Fury, and General Idea were central to the visibility of the AIDS epidemic, condemning the government for its silence. Galleries and museums, too, participated in the outcry as a generation of artists died off. Cities were littered with posters and propaganda: a poster for an ACT UP demonstration accused, “The government has blood on its hands, one AIDS death every half hour.” The bold text framed a large, bloody handprint. Red handprints, mimicking the posters, showed up on New York City mailboxes, as if people were literally dying in the streets. Gran Fury bus ads in Chicago showed three queer, interracial couples and read, “Kissing doesn't kill: greed and indifference do.” These sorts of actions were instrumental in shifting the public rhetoric to challenge the government to release funding to combat the epidemic.

Instagram post of bloody handprint

link

Instagram post of red handprint

link

on museum activism

The MCA, like many museums and cultural organizations, has continued to reflect upon these themes. In recent years, Gran Fury's bus ads again appeared throughout Chicago to promote This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, the MCA's exhibition of 1980s artworks that responded to the AIDS crisis, gender politics, and other issues of the period. Body Doubles furthered explored questions about the relationship between the body and identity.

This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, MCA Chicago, 2012. Chicago Transit Authority banner placements, featuring Gran Fury, Kissing Doesn’t Kill,1989

Photo: Titan Outdooron museum activism cont’d

And yet, even though museums around the world continue to remember those who have died of AIDS and promote awareness of the ongoing crisis with A Day Without Art, the position of advocacy common in the 1980s experienced a rhetorical shift toward impersonal civility. Today, in the name of awareness, we brandish pink for breast cancer and change our social media avatars in response to tragedy. The power of visibility campaigns to change policy should not be understated; visibility is imperative—a prerequisite for change—but it seems as if the momentum of 1980s activism has been replaced with a sense of complacency, as if visibility itself is enough.

Instagram post on museums and pride

link

Instagram post of Stonewall Inn

link

on activism

In the wake of Orlando, on the anniversary of Stonewall, we should reexamine the role of museums today. Must we wait to catalogue how artists record and respond to the major tragedies of our day, or are we able to the lead and challenge the cultural community to respond? It feels like we have some obligation to speak up but we’re waiting to see who will lead the charge.

Note

This post reflects the views of an anonymous staff member at the MCA.