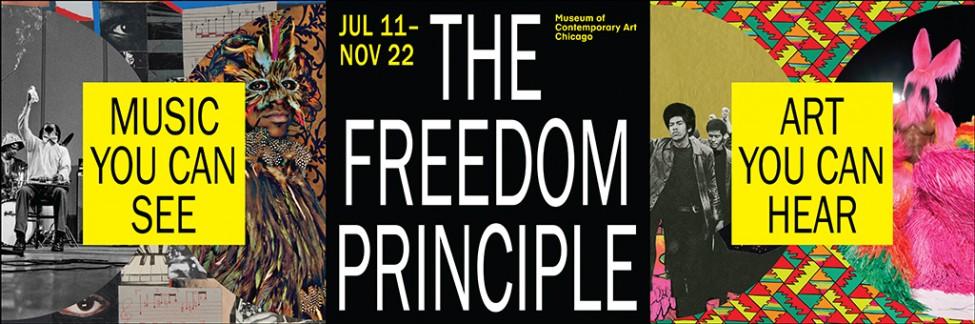

Art You Can Hear, Music You Can See

Mockup of billboard ad

© MCA ChicagoThe MCA doesn't employ any in-house writers, which means that we often draw from our talented staff to write such things as magazine articles, blog posts, and ad copy. Our Editor Lindsey Anderson reflects on the creative process surrounding writing for our Freedom Principle campaign.

Before coming to the MCA, I'd written for a few print publications and websites, but I had no experience writing copy for ads. For that reason, I am always equal parts perplexed and intrigued when I hear our communications team talk about our marketing strategies. As they throw out words like “proof points,” “call to action,” or “visual storytelling” and start passing around creative briefs, I start to feel like I'm on the set of Mad Men.

And so I was thrilled when the team invited me to work on a marketing campaign for The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now. “We need someone to draft a few lines of copy for the campaign,” they said. I’m going to be the next Don Draper, I thought.

In a meeting later that week, they talked about the exhibition and the campaign they wanted to build around it. I jotted down a few notes, reminding myself to read up on some of the names they mentioned—AfriCOBRA and the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). And then I skipped off, certain that I could come up with some clever tagline that would convince everyone in Chicago to see the show.

The next morning, I put my impressive Googling skills to work. I learned that many AACM members were also fine artists, and many AfriCOBRA members were musically inclined: Roscoe Mitchell, a longtime AACM member best known as a jazz iconoclast, is also an active painter whose works have graced album covers and gallery walls alike. And Wadsworth Jarell, one of four founding members of AfriCOBRA, chronicles the Chicago jazz scene in his paintings, immortalizing many of its most influential musicians. In short, many of the artists and musicians featured in The Freedom Principle don't just visit the borderlands between art and music from time to time; they've taken up permanent residence there.

Wadsworth Jarrell, AACM, 1994. Acrylic on tempered Masonite; 48 x 96 in. (121.9 x 243.8 cm)

Photo: Adger Cowans, courtesy of the artistSo when I sat down to draft potential taglines for the campaign, I wanted to try to highlight the interdisciplinary nature of the exhibition—without actually use yawn-inducing phrases like highlight the interdisciplinary nature of the exhibition. After writing—and immediately erasing—a few terrible taglines, I finally settled on “Art you can hear, music you can see.” Short and sweet, I thought. Original, I thought.

Only later, after a few coworkers told me that they liked how self-referential the tagline was, did I realize that it wasn’t quite as original as I had thought . . .

In 1964, 30 art professionals and philanthropists banded together to establish a museum of contemporary art in Chicago. And in 1967, after purchasing and remodeling a building on East Ontario Street that had once been a bakery, a photography studio, and the corporate headquarters of Playboy Enterprises (but, for better or worse, never at the same time), they opened their doors to the public. According to a Time Magazine

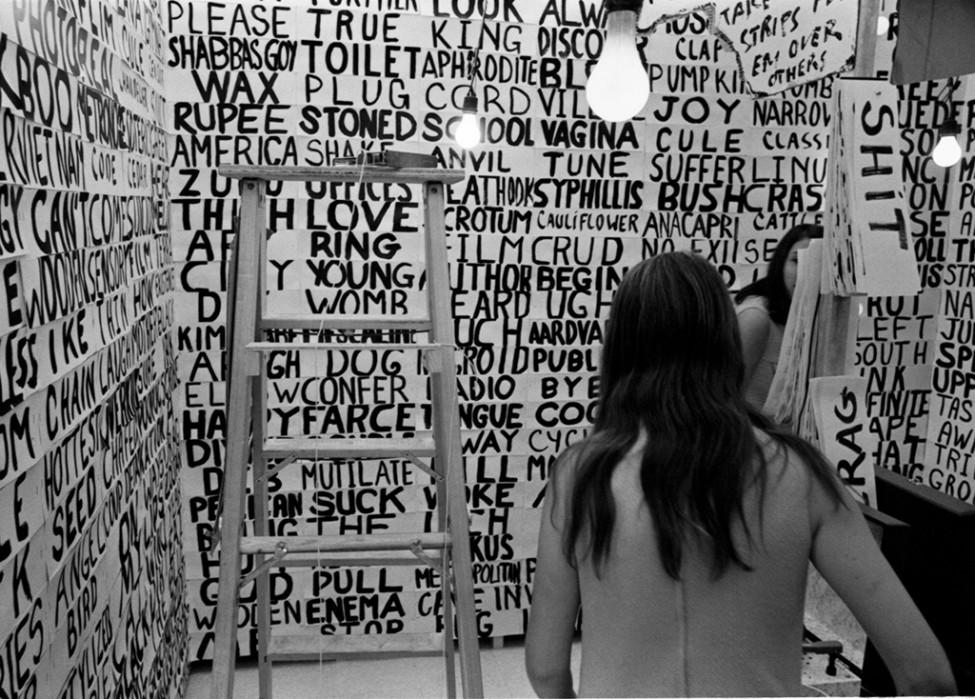

Pictures To Be Read/Poetry To Be Seen, as its name suggests, presented works by artists who blurred the line between words and images, literature and art. One of these artists, local legend and founding member of the Hairy Who, Jim Nutt, created fantastically detailed comic-book panels. Another, internationally renowned performance artist Allan Kaprow, re-created a 1964 Happening, encouraging visitors to “make poetry, make news” by stapling words and phrases to one of the gallery walls. Elsewhere in the museum, visitors also enjoyed a live performance by John Cage, an iconic composer known for muddling the distinction between art and music.

Installation view of Allan Kaprow's Happening from Pictures to Be Read, Poetry to be Seen, 1967

© MCA ChicagoIn other words, nearly 50 years ago, the founders of the MCA were already very much aware that artistic virtuosity isn't limited to paintings on walls or sculptures on pedestals. Exhibitions like Pictures To Be Read/Poetry To Be Seen and The Freedom Principle remind us that artists have long been bridging the divide between art and music, art and literature, art and life to more fully express themselves. And they remind us that every art form—painting, drawing, music, poetry, sculpture, dance, beat boxing—is, at its core, an expression of the human spirit.