At the Intersection of Science and Art

by Ken Walczek

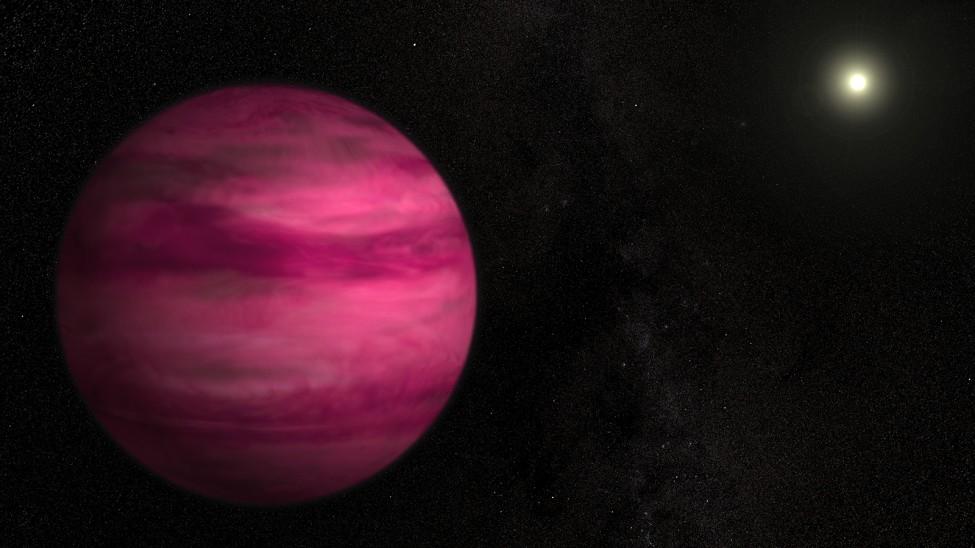

Artist's concept of exoplanet GJ 504b, 2013

© NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/S. WiessingerWe invited scientists from the Adler Planetarium to share new insights and perspectives on exhibitions at the MCA. Ken Walczek, the Adler's Far Horizons Lab Manager, shares his musings on science and art after viewing BMO Harris Bank Chicago Works: Sarah and Joseph Belknap, on view through February 24, 2015.

About

I have always viewed art with a scientific mind whether realizing it or not; always drawn to artists that approach their work with a systematic or even a scientific approach—Duchamp's Standard Stoppages come to mind. This personal revelation was inspired by a long discussion with friends following a visit to Sarah and Joseph Belknap's MCA exhibition and talk. Since my job at the Adler Planetarium involves science and engineering, this revelation may not seem so surprising, and it becomes even more clear when you discover that my roots and education were in the arts.

The earnest melding of art and science is a long overdue union fertile with potential. But it is also a marriage of two worlds with contrasting geographies of language and intention, both fraught with the need for navigation and cooperation.

Sarah Belknap and Joseph Belknap, Deflated Exoskin (1) (left) and Deflated Moon Skin (1) (right), 2014

Courtesy of the artistsAbout

Scientists frequently employ artists to visualize their discoveries. An explosion in the discovery of exoplanets (planets orbiting stars other than the sun) in the past few years has increased this pairing of artists and scientists to imagine these worlds according to the best interpretation of the data gleaned from observation. Perform an image search for “exoplanet” and you'll see dozens of examples. The intention is to make these distant worlds real for the scientists as well as the public, but these visualizations are speculative at best—meant only to inspire the imagination. The Belknaps interpret the surfaces of planetary bodies by exaggerating texture and color similar to the hired artists, yet they display them as deflated shells. They have goals other than accuracy in mind. It becomes an interesting contrast between conceptualization and interpretation—the world of the scientist versus that of the artist. The Belknaps' works, however, often toe this line between the accuracy of science and the impressions of art.

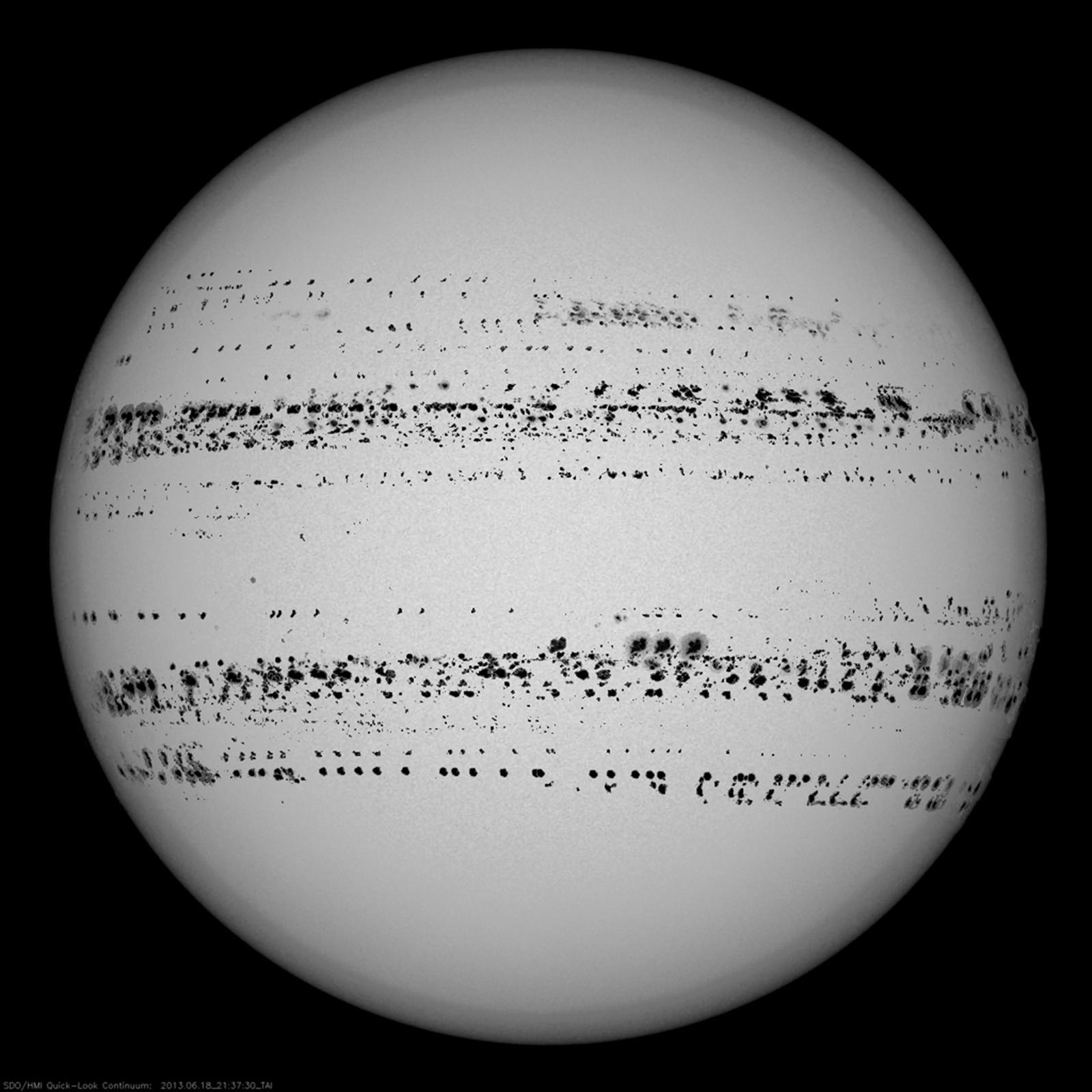

Sarah Belknap and Joseph Belknap, 4 months of Sun Spots, 2014

Courtesy of the artistsAbout

The work in the exhibition that ended up having the greatest impact on me was a tiny image tucked in a corner, dwarfed by their room-sized earth/moon crater work. The piece overlays four months of satellite images of the sun on a single sphere. It shows the motion and evolution of sunspots across its surface. It is an impressive piece mainly because it bridges the worlds of art and science so effectively. It is as informative as it is thoughtful. Yet it is not a work an astronomer would have made—that’s what makes it so impactful to my science brain. Instead, it is a demonstration of how artists, wittingly or not, can bring light to processes and patterns in the universe. It is informationally scrappy but visually dramatic. Astronomers think of sunspots (relatively cooler, thus darker, magnetic storms on the sun’s surface) not as blights but as part of a natural process and this work by the Belknaps demonstrates this idea that the sun is not a perfect sphere of light but that even its “imperfections” are shaped by physical processes. It is the mysteries of those processes that inspire astronomers to study it.

Artists are inspired by science and scientists are inspired by art. But this implies a gap. Science without the scientist is as incomplete as art without the artist. Where the land and the sea meet is where science and art should thrive. The geography at the intersection of science and art benefits best from shared exploration.