Hold Your Gun Arm Steady

by Brynn Hatton

Featured image

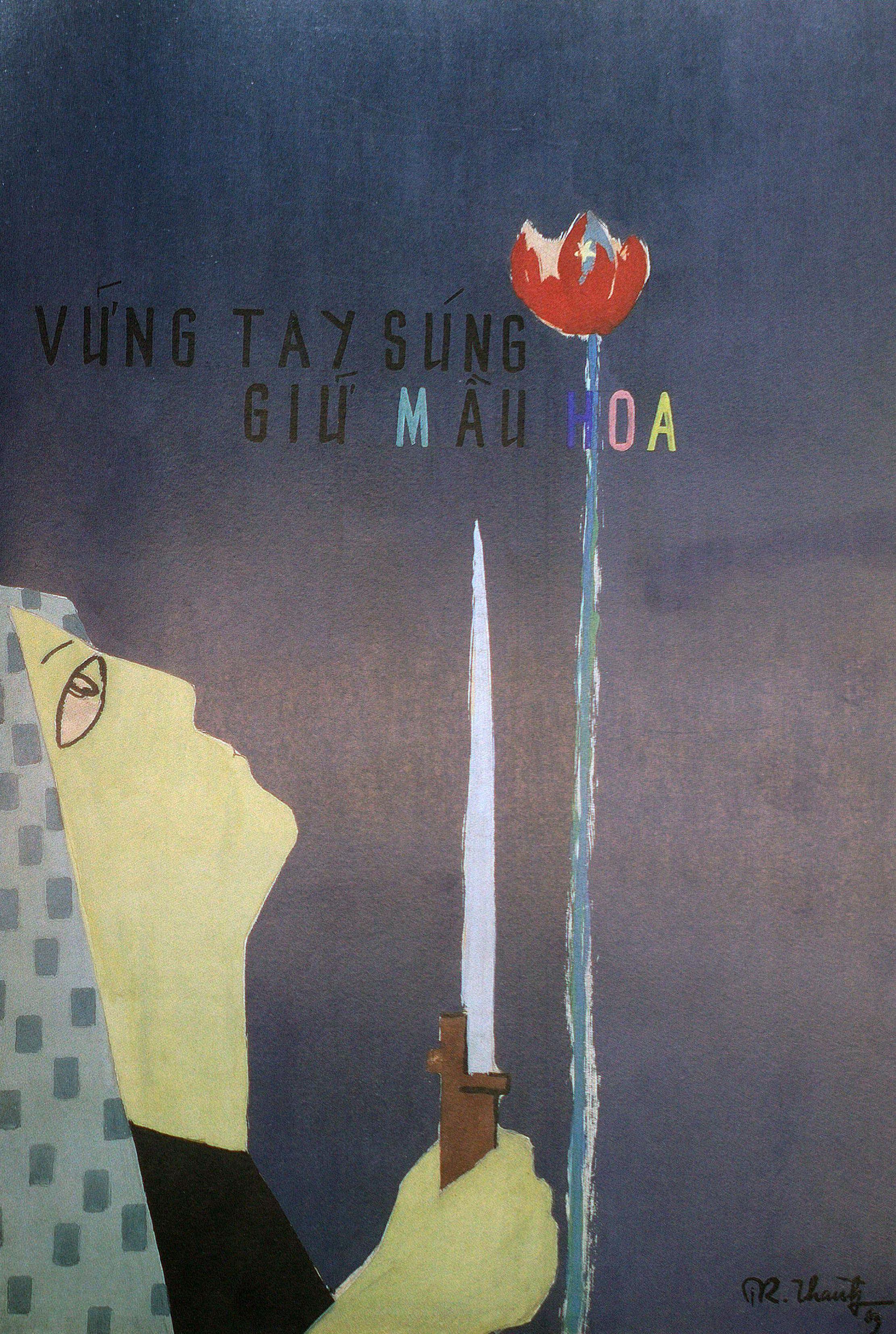

Poster with inscription translated as “Hold your gun arm steady to keep the color of the flower,” 1969, signed by “Tr. Thanh.” Courtesy of the Dogma Collection, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; reproduced in A Revolutionary Spirit: Vietnamese Propaganda Art from the Dogma Collection, exh. cat., January 8–18, 2015 (Hanoi: Vietnam Fine Arts Museum, 2015)

How do you disarm a metaphor? Does a steady flower need an even steadier gun? Can a society freed by violence ever in fact be free, or will traces of the past always reemerge, resistant to every form and every transformation, always bearing the weight of the revolutionary paradox?

blog intro

In an interview with the MCA, The Propeller Group's Matt Lucero remarked that the gun business is "a machine running beyond anybody's power and we're stuck right in the middle of it." As loose gun laws and the right to bear arms become more and more contested, a trend is arising in contemporary art, of artists reacting to and aestheticizing the tools and histories of violence. In time for The Propeller Group's closing weekend at the MCA, Brynn Hatton reflects on Vietnamese artworks that feature the AK-47—the icon and weapon par excellence of Third World and insurgent revolution.

on vietnamese propaganda

“Hold your gun arm steady to keep the color of the flower,” reads a revolutionary poster made in Vietnam, circa 1969. The subjects of the work—a red flower in mid-bloom, a female guerrilla soldier, and the rifle she grips in her right hand—occupy a cool, monochrome background of deep blue-gray. The vertical axis of the gun’s bayonet draws the eye upward to the vibrant petals of the straight-stemmed, strident, and supernaturally tall flower. Though it takes up very little surface area and sits right-of-center in a composition mostly weighted to the left, this flower is unquestionably the gravitational center of the work. The poster is both typical and exceptional of Vietnamese revolutionary art made during the Vietnam-American war. It is hand-painted, as most Vietnamese propaganda art was at the time, due to a lack of available printing technology in the country. It captures a sense of revolutionary optimism and collective spirit rather than express violence or hatred toward the enemy. But what makes this particular Vietnamese poster uncommon is the subtlety of its message and execution, and the rhetorical weightlessness with which it conveys perhaps the heaviest paradox of the revolutionary experience: that the future depends, in no small measure, on people’s willingness to kill and to die.

The gun that splits the poster’s composition straight down the middle, dividing the armed struggle of the present from the opening blossom of the future, is the ubiquitous icon of modern revolution: the AK-47. As one of the most widely used weapons in the world, especially in socialist countries and in third-world anti-colonial movements, a number of contemporary artists, including The Propeller Group and Le Brothers, have refashioned the AK-47 or Kalasknikov (so nicknamed after its inventor, Mikael Kalashnikov) in order to take its loaded past—as both a symbol and a weapon—and push it even further, in some cases even driving the gun’s associations into entirely different metaphorical spaces. Many of these works exist as multistage projects, conceived over a number of years and incorporating many different media, as if the object itself has become too oversaturated with reference to succeed as just one type of artwork.

Video

Video

on the propeller group

In The Propeller Group's The History of the Future

Le Brothers, installation view, The Game 2013

Le Brothers, still from The Game 2013

on Le Brothers

Le Ngoc Thanh and Le Duc Hai, two Vietnamese artists and identical twins who collectively make work under the moniker Le Brothers, have embarked on a similar multiyear, multistage journey to transform the AK-47's iconography, to inject it with new meaning and buoyancy. Their latest effort culminates in The Game

Le Brothers, still from The Game 2013

Video

conclusion

In these historic and contemporary artworks from Vietnam, the persistent draw toward the future and the backward pull of the past struggle to find mutual coherence in the iconic AK-47. It is an icon that seems to buckle under its own existential weight, yet it continues to reemerge, sending signals to an unknown future where an impossible world might one day take shape and hold steady.

The Propeller Group closes this Sunday, November 13. Le Brothers, The Gameis open through February 19, 2017 at the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok, Thailand.